Should I Reject This Participant? How to Fairly Identify Low-Quality Research Participants

By Josef Edelman, MS, Aaron Moss, PhD, & Cheskie Rosenzweig, PhD

When a research participant submits a survey, you, as the researcher, have a few options. You can accept the submission, in which case the participant gets paid and their approval rating increases. Or, you can reject the submission, in which case the participant is not paid and their reputation suffers (i.e., their approval rating goes down). On Connect, there is also an option to reject participants but still pay them—this is sometimes a requirement by Institutional Review Boards (IRBs).

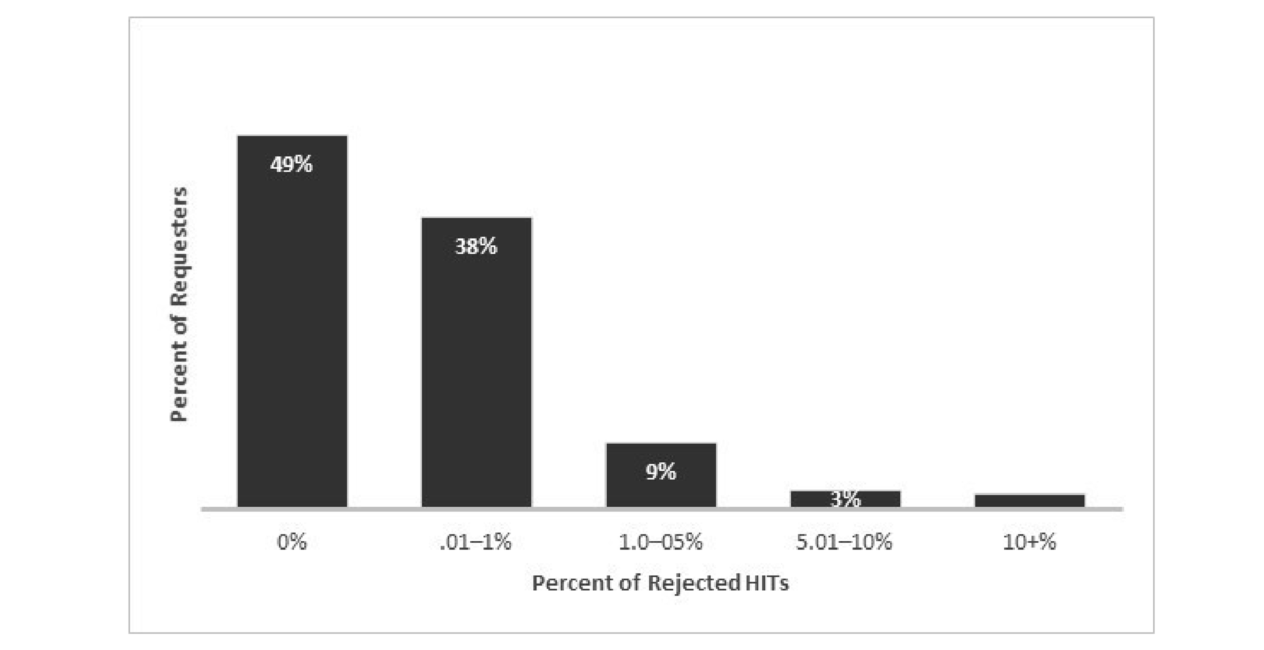

Academic researchers are often reluctant to reject participant submissions because of constraints imposed by IRBs and concern for participants’ welfare. Both concerns are reasonable. Yet, when researchers fail to reject clearly fraudulent submissions, bad actors are able to exploit the system. Data from CloudResearch indicate that almost 90% of researchers reject less than 1% of submissions on MTurk (Figure 1). And, only 4% of researchers ever reject more than 5% of submissions.

While the practice of accepting all submitted work protects participants from potential mistreatment, if low-quality tasks aren’t ever rejected, this can have negative consequences on the well-being of online platforms as a whole. First, many researchers rely on participants’ reputations to help them avoid low-quality respondents. When participants are rejected, their reputation is also downgraded in addition to not being paid (these systems work slightly differently on different platforms, but most have this mechanism in place). Multiple rejections downgrade participants’ reputation to the point where they become ineligible for most studies, effectively quarantining workers who are not paying attention or trying to game the system. Research has shown that MTurk workers with low reputation ratings are indeed much more likely to provide random data in psychology studies (Peer et al, 2014). Thus, rejecting such participants provides protection to the research community as a whole by keeping bad actors from participating in research studies. When such participants are not rejected, their reputations remain intact and their fraudulent behavior is continuously reinforced.

We provide guidelines below for when we believe there are valid grounds to reject a participant’s submission.

Valid Reasons for Rejecting a Respondent’s Submission

Straight-lining:

This occurs when a respondent selects the same answer in a straight line for every question – potentially exhibiting the respondent’s lack of attention for the task.

- Straight line responses are, sometimes, completely reasonable. For example, the image below displays a set of questions where a straight line of responses would be plausible. Anyone who loves sports may find themselves answering in the manner below.

- In order to reject a respondent for providing a straight-line response, the answers choices need to indicate the respondent was not paying attention. For example, a straight line of answers in response to items that contain reverse-coded or antonymous statements may warrant a rejection – as these answers are not so plausible.

Because straight-lining is so easily spotted by the researcher, participants who are not paying attention seldom provide straight line responses. However, straight-lining is clear grounds for a rejection when it shows the participant was not reading items in the study.

Speeding:

A respondent completes a task at an unrealistic pace – exhibiting the respondent’s lack of attention for the task.

- Deciding how fast is too fast to complete a survey is unclear. Some experienced participants can provide excellent data even at high speeds. Some research has shown that completion speed is not a straightforward and reliable indicator for survey quality (e.g. Buchanan, & Scofield, 2018) and that fast respondents often have quality comparable to the rest of the sample (Downs, 2010; Goddman, 2014). However, when page timing data shows that a participant spent only a few seconds on a page that required reading a manipulation or answering a long matrix of questions there are grounds for a rejection. Determining whether or not to reject a participant that completed a task at an unnaturally quick speed, should only be judged in tandem with other data quality measures like performance on attention checks, straight-lining, and overall data quality.

Open-Ended Responses:

When a respondent either provides gibberish or fails to follow a clear set of instructions for an open-ended response question, this can be grounds for rejection.

- Such failures typically exhibit the respondent’s lack of attention to the task, or an unwillingness to do what was asked of them. Even open-ended responses however, are not always by themselves the best indicators of data quality. For example, if a respondent appears to have good data quality across 99 questions in a survey, but leaves a single open ended question blank, we would not recommend rejecting such a participant.

Other examples of grounds for rejection are copy and pasted responses, responses that bear no relation to the question prompt, or responses that are often indicative of inattentive or otherwise low-quality participants including “NICE,” “GOOD,” and “GOOD SURVEY.”

Failing Attention Checks:

A respondent fails a valid attention check – exhibiting the respondent’s lack of attention for the task.

We recommend only using attention checks that have previously been validated as accurately measuring attentiveness and data quality. Although it may seem like attention check questions were all created equal, research has shown that it isn’t so simple to create good check questions. Questions that are thought of as attention checks don’t always measure attention and data quality. Some questions may instead be measuring memory, vocabulary level, or even culturally-specific knowledge that participants should not be expected to have. Because of this, pass rates on some attention checks are correlated with certain demographic factors such as, socioeconomic status, education, and race. Additionally, research has shown that some attention checks will be failed even by careful and attentive participants who may interpret a question in different ways than researchers intended.

We also do not recommend using questions that are written in a crafty way to catch participants who do not read every single word extremely carefully. These “gotcha” type questions are challenging even for well-meaning and attentive respondents, and do not take into account the fact that respondents, no matter how they are recruited, are human beings who by nature have shifting attentions and are not perfect.

There can be great variability in what some attention check questions measure, and the difficulty of attention checks is not always straightforward. Therefore, we do not recommend rejecting participants for failing a single attention or manipulation check. However, when participants fail multiple, straightforward and simple attention checks there may be grounds for a rejection. Like speeding or straight-lining, performance on attention checks is often best considered alongside other measures of data quality.

Rejections Should Never Come as a Surprise

It is important that participants understand potential rejection criteria before entering a study. Although some kinds of rejections may be based on data that are obviously fraudulent or in clear instances where participants did not complete the task, whenever possible, give very clear instructions to participants to guide them in how you’d like them to complete your survey. Not only will this create an objective standard which participants can aim for, but giving clear instructions is a best practice that will help you get better data. For example, if you are collecting data on an open-ended question, you can set clear criteria for what you consider to be an adequate open-ended response. These criteria should be clear in the instructions. For example, you might include a minimum number of words, a minimum number of sentences, and a concrete example of an acceptable response. We also recommend giving participants an opportunity to redo the study if that is at all feasible. Whenever possible, when submitted work does not meet the study’s criteria you can contact participants, explain why they were rejected, and offer an opportunity to try again.

Summary

As mentioned throughout this blog, the best case for issuing rejections often comes from considering various pieces of information together. Participants who show evidence of not paying attention across multiple measures of quality are good candidates for rejection. And, whenever there is clear evidence of fraudulent behaviors, researchers should strongly consider the implications of not just what the consequences are of rejecting the submission but what the consequences are of approving fraudulent responses.

We hope these tips help you in your research! If you are tired of dealing with bad data, we have many solutions to help. Connect, CloudResearch’s premier participant recruitment platform, offers exceptionally high data quality, and at a lower price compared to competitors. Additionally, you can contact our Managed Research team and we can carry out all parts of your study, from setup, to data cleaning, to analysis. Our team is staffed with experts in recruitment methods and data quality and can help you get the most out of your research.