An MTurk Alternative: Data Quality Analysis of Mturk vs Online Panels

Social science research constantly evolves. In the early decades of the twentieth century, for example, social scientists often gathered data using archival records or conducting experiments and interviews with members of the community. Then, in the 60s and 70s, academic departments started creating student subject pools in which students taking introductory classes on a particular topic were required to participate in research. In the 90s and 2000s came the internet and online data collection. Currently, most social science disciplines are in the midst of a technological revolution in which the internet is giving researchers access to a more diverse group of research subjects than ever before.

For many academic researchers, the technological revolution has primarily meant sampling from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. In less than a decade, MTurk has gone from a new source of data to a routine one; today hundreds of peer-reviewed papers are published each year with data collected from MTurk.

However, even though MTurk offers some advantages over more traditional subject pools, MTurk has its own limitations. In this blog, we introduce a new, alternative source of research participants—online research panels—and highlight the pros and cons of both online panels and MTurk as a place to recruit research subjects.

Mechanical Turk: A Well-Known Source of Research Participants

Mechanical Turk has been used by social scientists since at least 2011 (Buhrmeister, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011). Due to its popularity among academics, the research community has learned a lot about MTurk in a short time. For example, several studies have shown that MTurk workers are more diverse than student subject pools (Casey, Chandler, Levine, Proctor, & Strolovich, 2017; Huff & Tingley, 2015), a source of quality data (Shapiro, Chandler, & Mueller, 2013), and willing to work on long tasks for which it would be hard to find volunteers. At the same time, however, MTurk workers are not representative of the US population, may have extensive experience completing social science studies, and some groups of people are difficult or impossible to sample because they are underrepresented on the platform.

Prime Panels: A New Alternative to Amazon’s Mturk

Although many academics use Mechanical Turk to recruit research participants, there are several other sources of online participants known as online panels. Online panels are primarily used by researchers in industry. For example, within the market research industry, online participant recruitment has developed into a multi-billion dollar enterprise (Callegaro, Villar, Krosnick, & Yeager 2014). Driven by the demands of market research companies, these online panels have tens of millions of participants worldwide and some panels focus specifically on recruiting hard to reach demographic groups. Thus, online research panels likely have two advantages over MTurk. Because of their size and focus, online panels are likely much more diverse than MTurk. In addition, because online panels have not been used extensively by academic researchers, participants in these panels are likely unfamiliar with the measures and manipulations common in academic studies.

Comparing MTurk and Online Panels

At CloudResearch, we have recently published a paper comparing MTurk to a source of online panels known as Prime Panels. Given the issues discussed above, we sought to investigate whether participants on Prime Panels were more representative of the US population than those on MTurk and whether Prime Panels participants were more naive to common experimental manipulations within academic research than participants on MTurk. We also had a third goal: to see if we could find a way to improve the quality of data obtained from online panels.

Unfortunately, studies have consistently shown that participants from online research panels are less attentive and have lower scale reliabilities than MTurk workers (Kees, Berry, Burton, & Sheehan, 2017; Thomas & Clifford, 2017). This may be because building a panel with millions of people requires recruiting some participants who may be unmotivated to complete surveys or because the methods used by sample providers to identify poor respondents may be less efficient than the reputation system used by MTurk. Regardless of the reason, survey methods that can identify and remove poor respondents have the potential to turn online panels into a valuable resource for academic researchers. In our study, we sought to test the feasibility of a simple attention screener for this purpose.

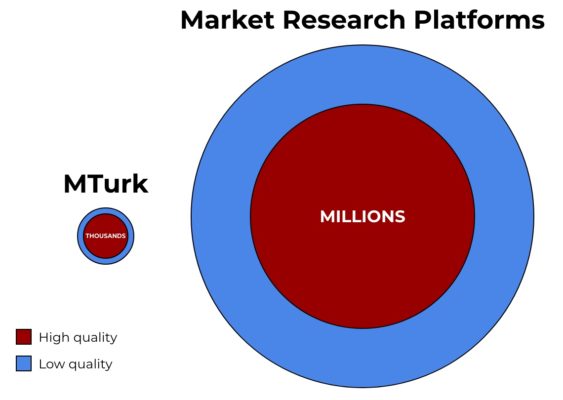

Figure 1 provides a visual depiction of what we expected the online research landscape to look like. From previous studies, we know there are under 100,000 active MTurk workers in the US and that most of these people provide quality data. We also know that online panels have tens of millions of participants, but that as much as 30 or 40% of these participants are inattentive. Thus, we sought to examine whether quality data can be obtained from online panels once inattentive participants are removed from the sample.

In our study we instituted a four-question screener at the beginning of the study that asked participants to read a target word and select a synonym. For example, one question asked, “Which of the following words is most related to “moody”? We found that while 94% of MTurk workers passed the screener, only 68% of Prime Panels participants did so. Thus, in the rest of our analyses, we examined our results by comparing three groups: MTurk participants who passed the screener, Prime Panels participants who passed the screener, and Prime Panels participants who failed the screener.

When examining data quality, we found clear differences among the groups. Participants who passed the screener also passed attention checks, had higher reliability scores on the BFI, and produced larger effect sizes on common experimental manipulations like the Trolley Dilemma, the Asian Disease problem, an anchoring task, and the Cognitive Reflection Task. In other words, our screener effectively separated quality respondents from inattentive and low-quality respondents on Prime Panels. And, quality respondents on Prime Panels produced data comparable in quality to MTurk workers.

In addition to examining differences in data quality, we looked for platform differences in demographic representativeness. We compared the demographics of our MTurk and Prime Panels samples to the American National Election Survey (ANES), a nationally representative, probability-based sample of Americans. As expected, Prime Panels participants were more representative of the country across many variables—age, marital status, number of children, political affiliation, and religious devotion—than participants from MTurk. This suggests that some groups of participants like older adults or those with more conservative values may be easier to recruit in online panels than on MTurk.

Finally, as expected, we found platform differences in participants’ previous exposure to the measures used in our study. As shown in Table 1, MTurk participants reported more prior exposure to three out of the four measures we used in our study than participants on Prime Panels. Differences in previous exposure were particularly pronounced for the Cognitive Reflection Task and the Trolley Dilemma.

| Sample | Cognitive Reflection Task | Trolley Dilemma | Asian Disease | Mt. Everest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTurk | 78.7% | 61.2% | 25.3% | 5.6% |

| Prime Panels - Passed | 19.1% | 11.0% | 6.9% | 6.6% |

| Prime Panels - Failed | 29.8% | 23.8% | 21.0% | 22.2% |

Altogether, the results of our study suggest that quality respondents can be separated from low-quality ones with the use of a simple screener. In addition, after filtering out inattentive respondents, online panels like Prime Panels may offer a more diverse and more naive sample of research participants than Mechanical Turk.

The Pros and Cons of Different Platforms

We see MTurk and online panels like Prime Panels as complementary sources of research participants. On Mechanical Turk, participants are willing to engage in difficult tasks that last several hours, to return for multiple waves of longitudinal data collection, and, generally speaking, they do so while providing quality data. On platforms like Prime Panels, participants are less willing to participate in long studies or longitudinal projects. But given the size of the platform, researchers are able to sample very narrow segments of the population. On Prime Panels it is possible to target participants in ways not possible on MTurk, like sampling people within specific US zip codes, by a range of occupations, or by matching to the US census. Although there are many questions about online panels that still need to be answered, their size, diversity, and lack of prior exposure to measures and manipulations common in academic research makes them an exciting new source of research participants.

References

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 3-5. doi:10.1177/1745691610393980

Callegaro, M., Villar, A., Yeager, D., Krosnick, J. &. (2014). A critical review of studies investigating the quality of data obtained with online panels based on probability and nonprobability samples. In M. Callegaro, R. Baker, J. Bethlehem, A. Goritz, J. Krosnick, & P. Lavrakas (Eds.), Online Panel Research: A Data Quality Perspective (pp. 23-53). UK: John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9781118763520.ch2

Casey, L. S., Chandler, J., Levine, A. S., Proctor, A., & Strolovitch, D. Z. (2017). Intertemporal differences among MTurk workers: Time-based sample variations and implications for online data collection. SAGE Open, 7, 1-15. doi:10.1177/2158244017712774

Huff, C., & Tingley, D. (2015). “Who are these people?” Evaluating the demographic characteristics and political preferences of MTurk survey respondents. Research & Politics, 2, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168015604648

Kees, J., Berry, C., Burton, S., & Sheehan, K. (2017). An analysis of data quality: Professional panels, student subject pools, and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Journal of Advertising, 46, 141-155. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1269304

Shapiro, D. N., Chandler, J., & Mueller, P. A. (2013). Using Mechanical Turk to study clinical populations. Clinical Psychological Science, 1, 213-220. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702612469015

Thomas, K. A., & Clifford, S. (2017). Validity and Mechanical Turk: An assessment of exclusion methods and interactive experiments. Computers in Human Behavior, 77, 184-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.08.038